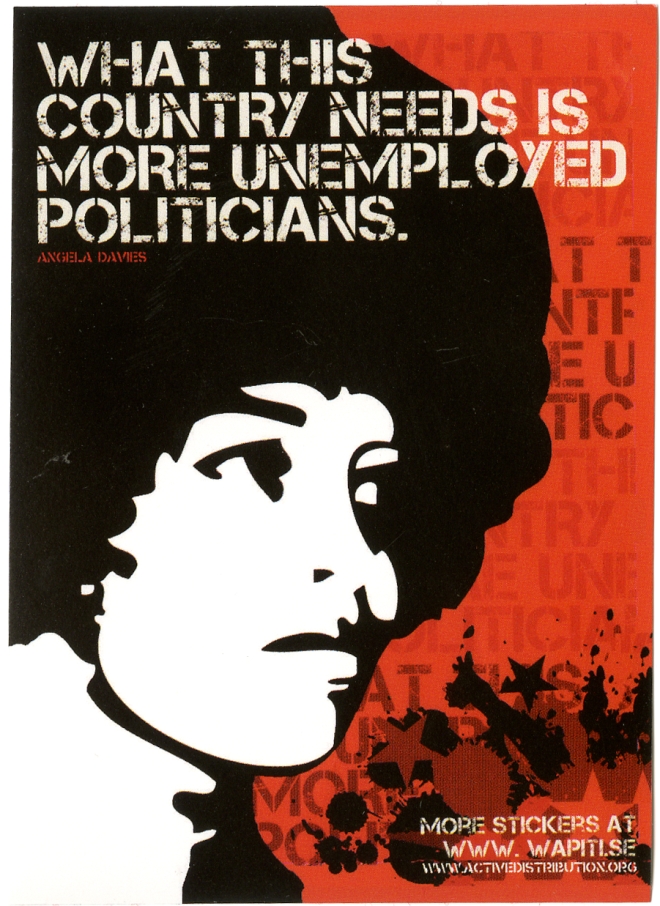

Angela Davis e o significado da liberdade – por Eduardo Carli para A Casa de Vidro

ANGELA DAVIS: O SIGNIFICADO DA LIBERDADE

“O principal desafio a ser enfrentado no ativismo é responder plenamente às necessidades do momento e fazer isso de modo que a luz que se pretende lançar sobre o presente possa ao mesmo tempo iluminar o futuro.” (ANGELA DAVIS, Introdução de “Mulheres, Cultura e Política”, lançamento da Boitempo Editorial, 2017, 195 pgs.)

Por Eduardo Carli de Moraes / A Casa de Vidro

Quando busca rememorar os eventos que marcaram mais profundamente sua vida, Angela Davis traz à tona um trauma social que deixou funda cicatriz. Em 15 de setembro de 1963, em sua cidade natal – Birmingham, Alabama – fanáticos da Klu Klux Klan explodiram 15 bananas de dinamite em uma igreja batista, matando quatro garotinhas (caso relatado em minúcias pelo documentário Four Little Girls de Spike Lee [download torrent]).

Como lembra a matéria da Opera Mundi, “com sua grande congregação afro-americana, o local era ponto de encontro de líderes dos direitos civis, como o reverendo Martin Luther King, Jr.” Além das quatro meninas mortas – Denise McNair, de 11 anos, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson e Addie Mae Collins, todas com 14 anos – outras 20 pessoas ficaram feridas no atentado perpetrado pelos racistas de ultra-direita da KKK.

“Quando milhares de indignados e irados manifestantes negros postaram-se diante do cenário do crime, Wallace enviou centenas de policiais e corpos armados para reprimir a multidão. Dois jovens negros foram assassinados naquela noite, um pela polícia e outro por um grupo racista. Enquanto isso, a reação popular ao atentado continuava a crescer, chamando a atenção do mundo para Birmingham. Luther King enviou para os funerais de três das moças mais de oito mil acompanhantes.” (Opera Mundi)

No mês anterior às bombas em Birmingham – ou seja, em agosto de 1963 – o Martin Luther King tinha liderado uma mega-marcha, que tomou conta de Washington D.C., onde proferiu seu poderoso discurso “I Have A Dream”. No cenário político dos EUA, acirrava-se o movimento dos direitos civis e, no interior dele, os “rachas” entre a via pacifista e de inspiração Gandhiana, liderada por King, e a ala mais radical e guerrilheira, capitaneada por Malcolm X e os Panteras Negras.

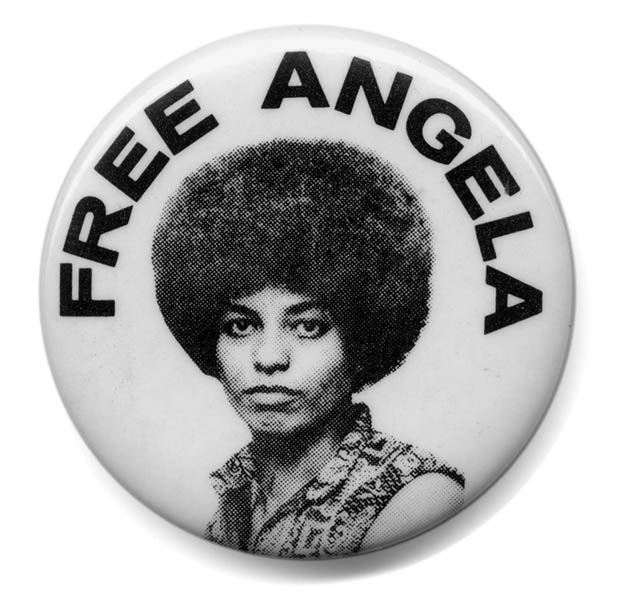

São nestas circunstâncias que começa a trajetória de Angela Davis como ativista, pensadora política, filósofa engajada, personalidade pública, força cultural e potência da natureza. O fogo que a anima é a indignação contra as atrocidades racistas. Crescendo na AmériKKKa, nação-líder no encarceramento em massa, Angela Davis perceberá bem cedo que a cor de seu pele ou seu exuberante cabelo afro tornavam-na possível alvo daquilo que ela teorizou sob o nome de Complexo Industrial-Prisional (em 1997, lançou um CD de spoken word, Prison Industrial Complex, que sintetiza com brilhantismo sua teoria crítica e práxis renovadora como uma das ativistas mais importantes de sua época).

Nas entrevistas reunidas no livro A Democracia da Abolição – Para além do Império, das prisões e da tortura (Ed. Difel), ela esclarece alguns elementos de sua análise sobre a “farra do aprisionamento” nos EUA, o país que lidera, disparado, o ranking do encarceramento em massa com mais de 2 milhões de pessoas detrás das grades (“mais de 70% deles são pessoas de cor”, p. 118):

“O uso da expressão complexo carcerário industrial por acadêmicos, ativistas e outros tem sido estratégico, criado precisamente para fazer eco ao termo complexo militar industrial. Quando se considera a dimensão com que ambos os complexos obtêm lucro enquanto produzem meios de mutilar e matar seres humanos, devorando recursos públicos, as semelhanças básicas tornam-se evidentes. Durante a Guerra do Vietnã, ficou evidente que a produção militar estava se tornando um elemento cada vez mais central da economia, um elemento que começara a colonizar a economia, por assim dizer. Podem-se detectar tendências similares no complexo carcerário industrial: ele não é mais um nicho menor para algumas empresas; a indústria da punição está no radar de incontáveis corporações nas indústrias de manufatura e de serviços… (p. 45-46)

A relação que normalmente se assume no discurso popular e acadêmico é que o crime gera castigo. O que tenho tentado fazer é encorajar as pessoas a aventar a possibilidade de que a punição, em síntese, pode ser vista mais como consequência da vigilância racial. As comunidades que são objeto de vigilância policial têm muito mais chances de fornecer indivíduos para a indústria da punição. Mais importante do que isso, a prisão é a solução punitiva para uma gama complexa de problemas sociais que não estão sendo tratados pelas instituições sociais que deveriam ajudar as pessoas na conquista de vidas mais satisfatórias. Esta é a lógica do que tem sido chamado de farra de aprisionamento: em vez de construírem moradias, jogam os sem-teto na cadeia. Em vez de desenvolverem o sistema educacional, jogam os analfabetos na cadeia. Jogam na prisão os desempregados decorrentes da desindustrialização, da globalização do capital e do desmantelamento do welfare state. Livre-se de todos eles. Remova essas populações dispensáveis da sociedade. Seguindo essa lógica, as prisões tornam-se uma maneira de dar sumiço nas pessoas com a falsa esperança de dar sumiço nos problemas sociais latentes que elas representam.” (47-48)

Esta obra – A Democracia da Abolição – contem uma série de entrevistas com Angela Davis concedidas logo após o escândalo do presídio de Abu Ghraib. A autora analisa como sistemas históricos de opressão tais quais a escravidão e o linchamento continuam a influenciar e solapar a democracia na atualidade. Davis se fundamenta na tese de W. E. B. Du Bois de que quando os negros se tornaram livres da escravidão nos EUA, negaram-lhes os direitos plenos de outros cidadãos e a criação de um sistema carcerário emergiu como uma maneira de manter o domínio e o controle sobre populações inteiras. Davis investiga a noção de uma Democracia da Abolição, ainda por vir, um conjunto de relações sociais livres da opressão e da injustiça. A obra vem acompanhada de prefácio de Eduardo Mendieta, professor de Filosofia da Stony Brook University.

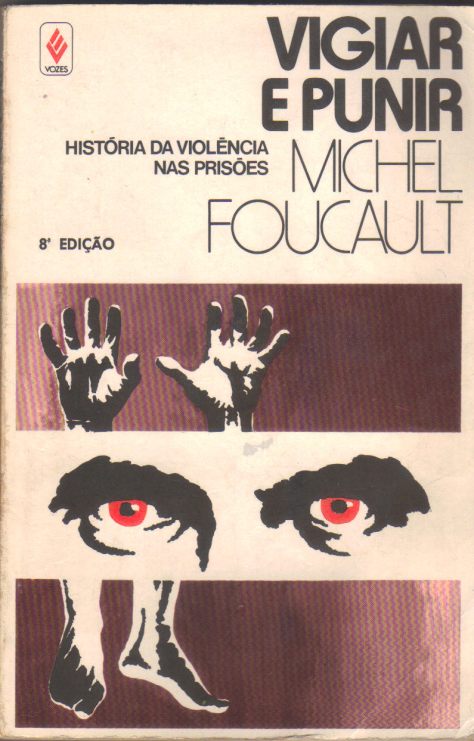

Quando entramos em contato com seus brilhantes diagnósticos e denúncias, ficamos tentados a dizer que Angela Davis realizou algo de importância sociológica e política comparável à realização intelectual tremenda de Michel Foucault em sua obra Vigiar e Punir – lque ela reconhece como uma de suas principais influências. No entanto, a ênfase de Davis está no fato de que “em todo o mundo o racismo esteve incrustado em práticas de cárcere”: “você descobrirá um número desproporcional de pessoas de cor e de pessoas do Sul Global encarceradas em cadeias e presídios.” (p. 82)

“A delinquência própria à riqueza é tolerada pelas leis e, quando lhe acontece cair em seus domínios, ela está segura da indulgência dos tribunais e da discrição da imprensa.” (MICHEL FOUCAULT, Vigiar e Punir, p. 239)

Falando de experiência própria – esteve encarcerada na solitária, por 15 meses, e esteve na lista dos 10 “Most Wanted” do FBI -, Angela Davis denuncia um sistema perverso que encarcera em massa e nisso ganha lucros estratosféricos. Critica a privatização das cadeias, ou seja, os booms da construção civil responsáveis por “aquecer a economia” através da construção de novos presídios. Oferece demonstrações às mancheias do quanto as prisões praticam o racismo institucionalizado (uma face recorrente da “banalidade do mal” de que fala Hannah Arendt). Expõe e explicita o quanto a chamada Guerra às Drogas é uma perversa maquinaria de estigmatização e aprisionamento desta demonizada figura do traficante de entorpecentes (confiram também, sobre este tema, a obra Acionistas do Nada, de Orlando Zaconne, e The New Jim Crow / A Nova Segregação, de Michelle Alexander).

Angela Davis vê não apenas vestígios do sistema escravista nas prisões: enxerga uma continuidade histórica que conduz à defesa que ela faz de que hoje, em pleno século 21, precisamos de um novo movimento abolicionista. Na companhia de outros teóricos atuais (como Christian Parenti), ela desvelou a prisão como instituição criada para Punir os Pobres (para citar o título de uma obra do sociólogo Löic Wacquant).

“A abolição das prisões exige que reconheçamos o grau em que a nossa atual ordem social precisará ser radicalmente transformada. (…) Quando me refiro à abolição dos presídios, gosto de citar a noção de Du Bois sobre democracia da abolição, que significa falar não unicamente, nem fundamentalmente, sobre a abolição como um processo negativo de demolição, mas também como um processo de construção, de criação de novas instituições. (…) Um mundo sem prisões é concebível…. atrelada à abolição dos presídios, está a abolição dos instrumentos de guerra, a abolição do racismo e a abolição das circunstâncias sociais que levaram homens e mulheres pobres às forças armadas como seu único caminho de fuga da miséria, da falta de moradia e de oportunidades.” (p. 88)

‘Democracia da abolição’ é uma expressão utilizada por Du Bois em seu livro ‘The Black Reconstruction’, seu estudo germinal sobre o período imediatamente posterior à escravidão… Du Bois sustentou que a fim de alcançar a abolição abrangente da escravidão – após a instituição ter se tornado ilegal e os negros libertos de suas correntes -, novas instituições deveriam ter sido criadas para incorporar os negros dentro da ordem social. (…) Precisavam de acesso a instituições de ensino e precisavam reivindicar o voto e outros direitos políticos, um processo que começara mas que permaneceu incompleto, durante o curto período de reconstrução radical que terminou em 1877.” (p. 113)

Autora de uma obra seminal chamada Are Prisons Obsolete? (As Prisões São Obsoletas?), Angela Davis defende a possibilidade de um ativismo focado na “obsolescência do encarceramento como forma dominante de castigo”, mas ressalva: “não podemos fazer isso brandindo machados e investindo literalmente contra os muros dos presídios, mas sim reivindicando novas instituições democráticas que discutam os problemas que nunca são discutidos pelos presídios de maneira produtiva.” (p. 89)

A lei atual seria viciada e cega, segundo Angela Davis, já que “incapaz de levar em consideração as condições sociais que tornam certas comunidades muito mais suscetíveis ao encarceramento do que outras”: “a lei não se importa se esse indivíduo teve acesso a uma boa educação ou não, ou se ele/ela vive sob condições de pobreza porque fábricas em suas comunidades fecharam as portas e se mudaram para um país de Terceiro Mundo, ou se pagamentos da previdência social disponíveis anteriormente chegaram ao fim. A lei não se importa com as condições que levam algumas comunidades a uma trajetória que torna as prisões inevitáveis. Embora cada indivíduo tenha direito a um processo adequado, a chamada cegueira da justiça possibilidade que o racismo latente e preconceitos de classe resolvam a questão de quem tem que ser preso ou não.” (p. 111)

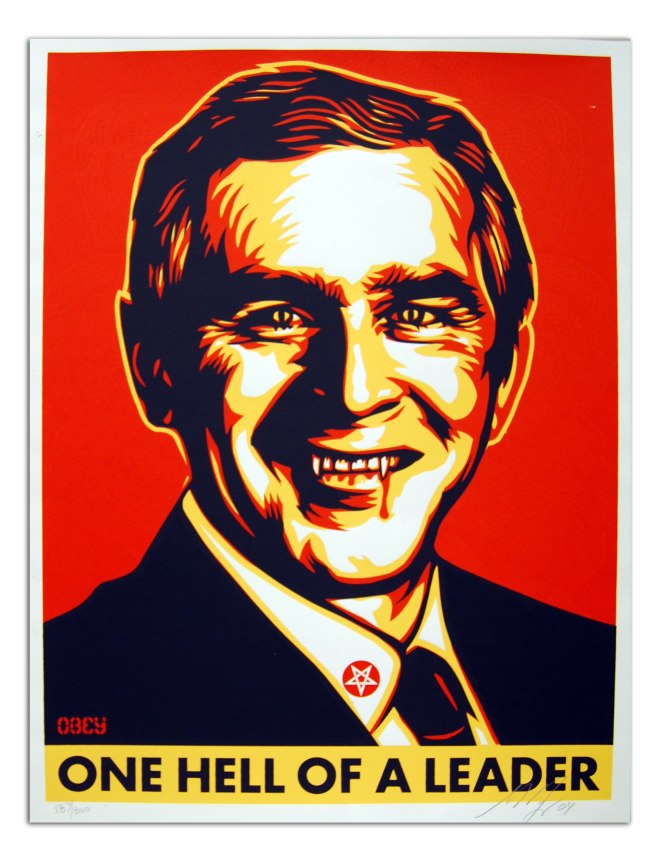

Angela Davis também realiza uma crítica contundente da política imperialista dos EUA na era pós-11 de Setembro, com a agressão militar ao Afeganistão e ao Iraque levada à cabo pelo militarismo chauvinista W.A.S.P. do regime Bush Jr. Sabemos o quanto a carniceria genocida promovida pelo governo Bush esteve calcada numa doutrina maniqueísta de um simplismo idiótico, que alimentou violentas ondas de islamofobia, de xenofobia, de perseguição racista aos “árabes”, com uma maré de violações dos direitos humanos de imigrantes, de encarceramentos baseados em falácias racistas e preconceitos, de torturas praticadas contra supostos “terroristas” que assim foram rotulados simplesmente por suas aparências ou por suposições absurdas de conexões inexistentes com Al Qaedas, Estados Islâmicos ou outras encarnações do Eixo do Mal.

Do mesmo modo que, durante a Guerra do Vietnã, os horrores perpetrados pelos ianques na Indochina tinham como símiles domésticos as atrocidades cometidas contra ativistas nos EUA (como o assassinato de 4 estudantes em Ohio num rally anti-guerra), no cenário atual também há uma similitude entre as torturas praticadas em Guantánamo e Abu Ghraib (dentre outras prisões militares) e o tratamento cotidiano infligido aos encarcerados no complexo carcerário industrial. Nestee, é vigente uma “violência cotidiana que é justificada como o meio diário de controlar as populações carcerárias nos Estados Unidos” (p. 136). São, em sua opinião, “sinais bem claros de políticas e práticas eminentemente fascistas” (p. 143) – Guantánamo e Abu Ghraib, longe de serem aberrações ou anomalias, são sintomas de um fascismo cotidianizado nas prisões, face atual da banalidade do mal.

RECOMENDADO: “The Road to Guantanamo” (Documentário de M. Winterbottom)

“Os presídios militares como Guantánamo tornaram-se possíveis pelo rápido desenvolvimento de novas tecnologias dentro dos presídios domésticos. Ao mesmo tempo, os presídios de segurança máxima foram possibilitados pelas torturas e tecnologias militares. Eu gosto de pensar nos dois como simbióticos. O centro de detenção militar como um local de tortura e repressão não substitui, portanto, o presídio de segurança máxima doméstico (que, de forma incidental, está sendo globalmente comercializado), mas, em vez disso, ambos constituem locais extremos onde a democracia perdeu suas reivindicações. (…) A tortura diária que é característica dos presídios de segurança máxima pode ter um poder de permanência mais longe do que o presídio militar ilegal…. Essa regularização, essa normalização, pode ser muito mais ameaçadora, especialmente porque é dada como certa e não considerada digna da atenção da mídia. As práticas dos presídios de segurança máxima nunca são representadas como as aberrações que Guantánamo e Abu Ghraib supostamente são.” (p. 146)

Discípula de Herbert Marcuse – o autor de Eros & Civilização, considerado como um dos mentores intelectuais para muitos revoltosos do Maio de 1968 francês – Angela Davis teve sólida formação filosófica. “Eu aprendi muito com Marcuse sobre a relação entre a crítica da filosofia e da ideologia; eu me inspirei particularmente em sua obra Contra-revolução e revolta” (D.A., p. 26). Angela estava iniciando uma promissora trajetória como professora de filosofia da UCLA (Universidade da Califórnia em Los Angeles), quando viu sua carreira docente sob ataque, posta na mira da perseguição política: um certo supremacista branco, ex-astro de Hollywood e futuro presidente dos EUA, Mr. Ronald Reagan – na época, governador da Califórnia – mobilizou suas forças e capangas para que Angela fosse demitida (Saiba mais sobre a controvérsia Reagan vs Angela Davis).

Herbert Marcuse e Angela Davis

A justificativa de Ronald Reagan para a perseguição política à Angela Davis foi esta: ela era afiliada ao Partido Comunista e ao Partido dos Panteras Negras (Black Panther Party). Além disso, Angela Davis também tinha ficado célebre por participar da campanha para libertar do cárcere os “Soledad Brothers“, três homens afrodescendentes acusados de assassinar um policial branco. Dentre eles estava o autor marxista e ativista radical George Jackson [1941-1971], que escreveu na prisão, de modo similar a Gramsci ou Graciliano Ramos, notáveis cadernos do cárcere, já que atrás das grades havia conhecido e estudado a obra de Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, Engels, Mao, dentre outros.

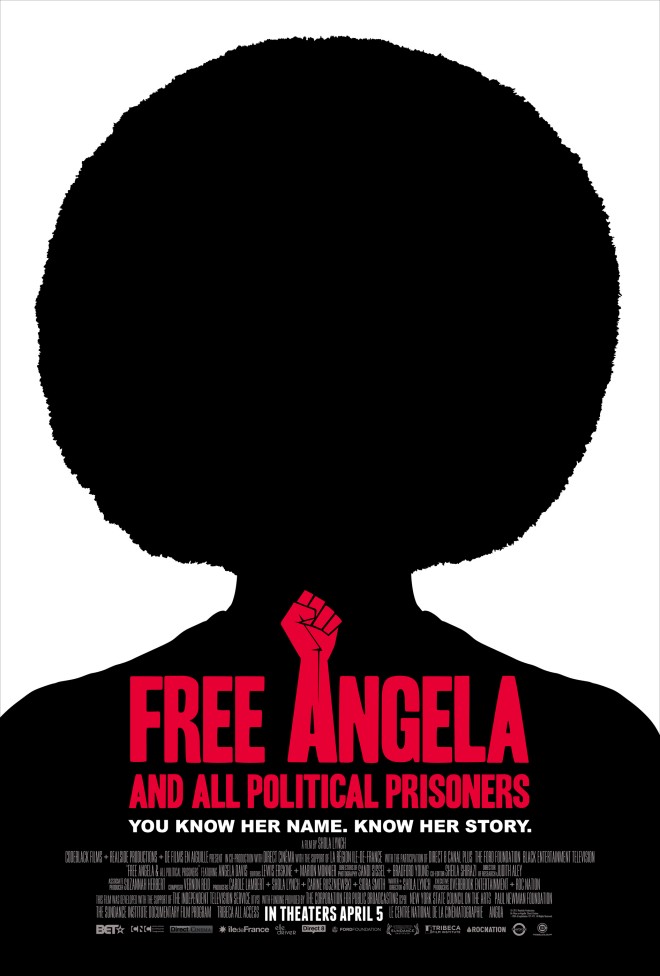

Em uma tentativa de fuga da cadeia, George Jackson e os Soledad Brothers acabaram mortos. Angela Davis foi acusada de ser cúmplice do jailbreak. Esteve presa e depois foi inocentada após um julgamento espetacular, ocorrido em 1972, narrado em minúcias no vibrante documentário Libertem Angela Davis (Free Angela and All Political Prisoners, 2012, de Shola Lynch).

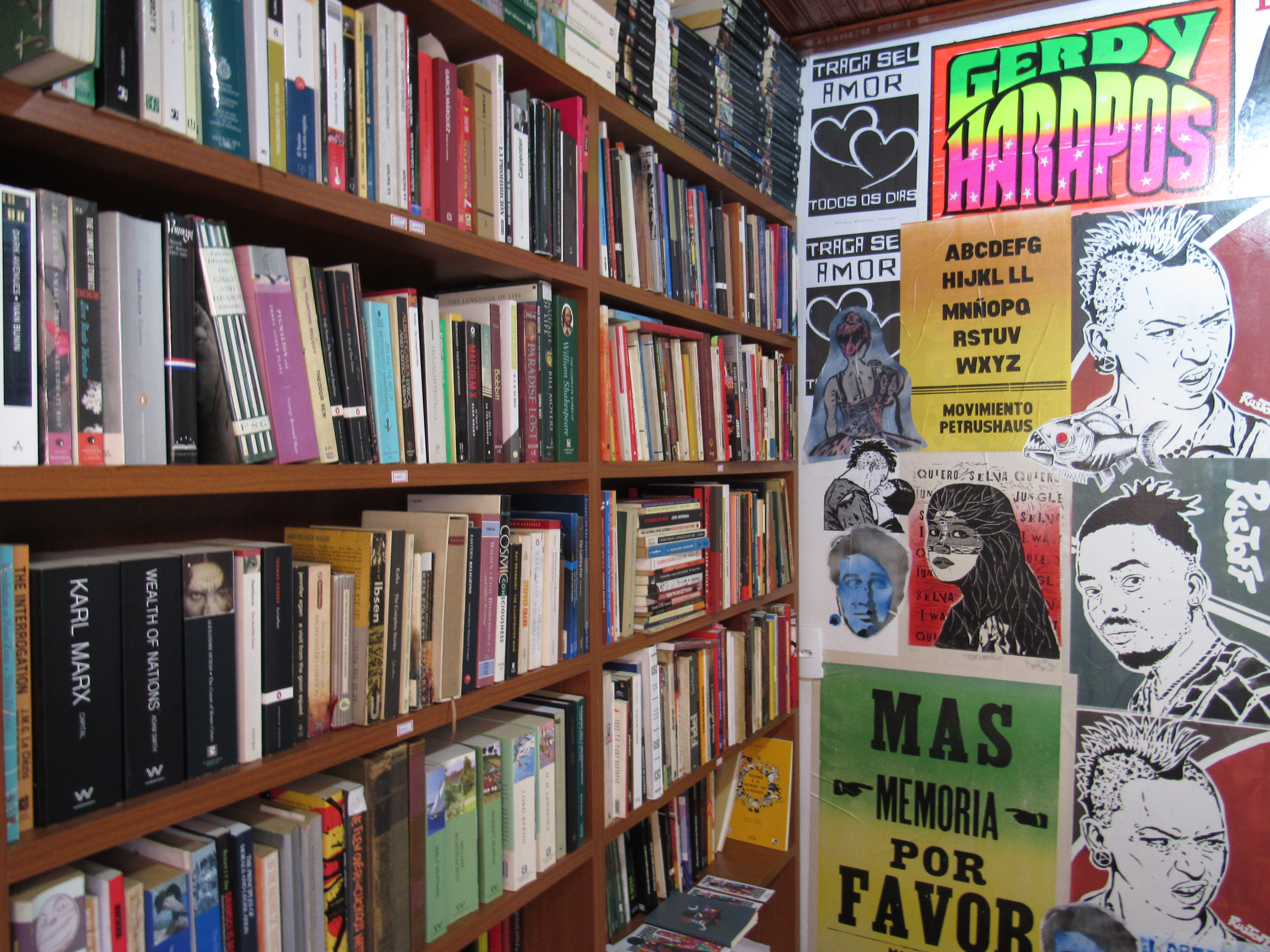

Apesar de toda a perseguição política e da tentativa reiterada dos poderes conservadores de calarem sua voz, Angela Davis prosseguiu sua corajosa jornada como educadora, ativista, escritora. Algumas de suas obras principais são: Angela Davis – An Autobiography (1974); Women, Race, and Class (1983); Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday (1999).

Como ativista pela libertação de presos políticos, como Nelson Mandela, Huey Newton, Ericka Huggins, Mumia Abu Jamal, mas também como alguém que vivenciou na própria pele a violência do sistema patriarcal, racista e misógino, Angela Davis destacou-se pela lucidez com que desvelou as entranhas de uma maquinaria cruel de opressões de classe, raça e gênero que sustenta as ditas “democracias” burguesas da atualidade.

Profunda conhecedora da produção artística e intelectual dos african americans – de pensadores e escritores como Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Dubois, Toni Morrison, Zora Neale Hurston, Paul Gilroy, Maya Angelou. Marcus Garvey; de cantoras e “divas negras” como Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith e Gertrude ‘Ma’ Rainey (trio quem dedicou um livro, Legados Do Blues e Feminismo Negro); de rappers e poetas-do-ritmo como Gil Scott Heron e os Last Poets; de grafiteiros e artistas plásticos e tantos outros criadores – Angela Davis é ela mesma uma força cultural de rara eloquência.

É uma voz que atiça o fogo das indignações incendiárias nos peitos daqueles que deixaram esta chama abrandar. Angela Davis comove por sua capacidade de inflamar o verbo com algo na vibe Rage Against the Machine, ainda que tenha também tanta delicadeza e generosidade, tanta humanidade e empatia. Tudo isto basta para torná-la, no mundo contemporâneo, na companhia de figuras como Cornel West e Alice Walker, uma indispensável voz afroamericana repleta de infindável sabedoria e intenso senso crítico.

* * * **

LEITURA RECOMENDADA:

Mulheres, Raça e Classe (Boitempo, 2016)

Mulheres, Raça e Classe (Boitempo, 2016)

COMPRAR NA LIVRARIA A CASA DE VIDRO

Descrição: Mais importante obra de Angela Davis, “Mulheres, raça e classe” traça um poderoso panorama histórico e crítico das imbricações entre a luta anticapitalista, a luta feminista, a luta antirracista e a luta antiescravagista, passando pelos dilemas contemporâneos da mulher. O livro é considerado um clássico sobre a interseccionalidade de gênero, raça e classe. Livro novo, em perfeito estado, 244 pgs. Comprar

* * * * *

LEIA TB:

TRECHOS DO LIVRO “O SIGNIFICADO DA LIBERDADE” (THE MEANING OF FREEDOM)

23 Sep 1969, Los Angeles, California, USA — Admitted Communist and UCLA philosophy instructor Angela Davis said at a press conference that she was fired for racist, not political reasons. — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

“Beware of those leaders and theorists who eloquently rage against white supremacy but identify black gay men and lesbians as evil incarnate. Beware of those leaders who call upon us to protect our young black men but will beat their wives and abuse their children and will not support a woman’s right to reproductive autonomy. Beware of those leaders! And beware of those who call for the salvation of black males but will not support the rights of Caribbean, Central American, and Asian immigrants, or who think that struggles in Chiapas or in Northern Ireland are unrelated to black freedom! Beware of those leaders!

Regardless of how effectively (or inneffectively) veteran activists are able to engage with the issues of our times, there is clearly a paucity of young voices associated with black political leadership. The relative invisibility of youth leadership is a crucial example of this crisis in contemporary black social movements. On the other hand, within black popular culture, youth are, for better or for worse, helping to shape the political vision of their contemporaries. Many young black performers are absolutely brilliant. Not only are they musically dazzing, they are also trying to put forth anti-racist and anti-capitalist critiques. I’m thinking, for example, about Nefertiti, Arrested Development, The Fugees, and Michael Franti…”

[youtube id=http://youtu.be/aIXyKmElvv8]

Listen to Fugee’s The Score (Full Album)

[youtube id=http://youtu.be/6VCdJyOAQYM]

Download Arrested Development’s album 3 Years, 5 Months & 2 Days in the Life Of…

[youtube id=http://youtu.be/DF3aK3XCgb4]

4 Michael Fanti’s albums for download in one single torrent

* * * * *

“There are already one million in prison in the United States. This does not include the 500.000 in city and county jails, the 600.000 on parole, and the 3 million people on probation. It also does not include the 60.000 young people in juvenile facilities, which is to say, there are presently more than FIVE MILLION people either incarcerated, on parole, or on probation… Not only is the duration of imprisonment drastically extended, it is rendered more repressive than ever. Within some state prison systems, weights have even been banned. Having spent time in several jails myself, I know how important it is to exercise the body as well as the mind. The barring of higher education and weight sets implies the creation of an incarcerated society of people who are worth little more than trash to the dominant culture.

Who is benefiting from these ominous new developments? There is already something of a boom in the prison construction industry. New architectural trends that recapitulate old ideas about incarceration such as Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon have produced the need to build new jails and prisons – both public and private prisons. And there is the dimension of the profit drive, with its own exploitative, racist component. It’s also important to recognize that the steadily growing trend of privatization of U.S. jails and prisons is equally menacing… We therefore ask: How many more black bodies will be sacrified on the altar of law and order?

The prison system as a whole serves as an apparatus of racist and political repression… the fact that virtually everyone behind bars was (and is) poor and that a disproportionate number of them were black and Latino led us [the activists] to think about the more comprehensive impact of punishment on communities of color and poor communities in general. How many rich people are in prison? Perhaps a few here and there, many of whom reside in what we call country club prisons. But the vast majority of prisoners are poor people. A disproportionate number of those poor people were and continue to be people of color, people of African descent, Latinos, and Native Americans.

Some of you may know that the most likely people to go to prison in this country today are young African American men. In 1991, the Sentencing Project released a report indicating that 1 in 4 of all young black men between the ages of 18 and 24 were incarcerated in the United States. 25% is an astonishing figure. That was in 1991. A few years later, the Sentencing Project released a follow-up report revealing that within 3 or 4 years, the percentage had soared to over 32%. In other words, approximately one-third of all young black men in this country are either in prison or directly under the supervision and control of the criminal justice system. Something is clearly wrong.”

* * * * *

“Black people have been on the forefront of radical and revolutionary movements in this country for several centuries. (…) Not all of us have given up hope for revolutionary change. Not all of us accept the notion of capitalist inevitability based on the collapse of socialism. Socialism of a certain type did not work because of irreconcilable internal contradictions. Its structures have fallen. But to assume that capitalism is triumphant is to use a simplistic boxing-match paradigm. Despite its failure to build lasting democratic sctructures, socialism nevertheless demonstrated its superiority over capitalism on several accounts: the ability to provide free education, low-cost housing, jobs, free child care, free health care, etc. This is precisely what is needed in U.S. black communities… and among poor people in general. Harlem furnishes us with a dramatic example of the future of late capitalism and compelling evidence of the need to reinvigorate socialist democratic theory and practise – for the sake of our sisters and brothers who otherwise will be thrown into the dungeons of the future, and indeed, for the sake of us all.

During the McCarthy era, communism was established as the enemy of the nation and came to be represented as the enemy of the “free world”. During the 1950s, when membership in the Communist Party of U.S.A. was legally criminalized, many members were forced underground and/or were sentenced to many years in prison. In 1969, when I was personally targeted by anti-communist furor, black activists in such organizations as the Black Panther Party were also singled out. As a person who represented both the communist threat and the black revolutionary threat, I became a magnet for many forms of violence… If we can understand how people could be led to fear communism in such a visceral way, it might help us to apprehend the ideological character of the fear of the black criminal today.

The U.S. war in Vietnam lasted as long as it did because it was fueled by a public fear of communism. The government and the media led the public to believe that the Vietnamese were their enemy, as if it were the case that the defeat of the racialized communist enemy in Vietnam would ameliorate U.S. people’s lives and make them feel better about themselves…”

- Saiba mais sobre a GUERRA DO VIETNÃ com o documentário de Peter Davis, Hearts and Minds (Corações e Mentes, Vencedor do Oscar)

“When a child’s life is forever arrested by one of the gunshots that are heard so frequently in poor black and Latino communities, parents, teachers, and friends parede in demonstrations bearing signs with the slogan ‘STOP THE VIOLENCE.’ Those who live with the daily violence associated with drug trafficking and increasing use of dangerous weapons by youth are certainly in need of immediate solutions to these problems. But the decades-old law-and-order solutions will hardly bring peace to poor black and Latino communities. Why is there such a paucity of alternatives? Why the readiness to take on a discourse and entertain policies and ideological strategies that are so laden with racism?

Ideological racism has begun to lead a secluded existence. It sequesters itself, for example, within the concept of crime. (…) I, for one, am of the opinion that we will have to renounce jails and prisons as the normal and unquestioned approaches to such social problems as drug abuse, unemployment, homelessness, and illiteracy. (…) When abolitionists raise the possibility of living without prisons, a common reaction is fear – fear provoked by the prospect of criminals pouring out of prisons and returning to communities where they may violently assault people and their property. It is true that abolitionists want to dismantle structures of imprisonment, but not without a process that calls for building alternative institutions. It is not necessary to address the drug problem, for example, within the criminal justice system. It needs to be separated from the criminal justice system. Rehabilitation is not possible within the jail and prison system.

We have to learn how to analyze and resist racism even in contexts where people who are targets and victims of racism commit acts of harm against others. Law-and-order discourse is racist, the existing system of punishment has been deeply defined by historical racism. Police, courts, and prisons are dramatic examples of institutional racism. Yet this is not to suggest that people of color who commits acts of violence against other human beings are therefore innocent. This is true of brothers and sisters out in the streets as well as those in the high-end suites… A victim of racism can also be a perpetrator of sexism. And indeed, a victim of racism can be a perpetrator of racism as well. Victimization can no longer be permitted to function as a halo of innocence.”

(pg. 29 – 31)

* * * * *

“The connection between the criminalization of young black people and the criminalization of immigrants are not random. In order to understand the structural connections that tie these two forms of criminalization together, we will have to consider the ways in which global capitalism has transformed the world. What we witnessed at the close of the 20th century is the growing power of a circuit of transnational corporations that belong to no particular nation-state, that are not expected to respect the laws of any given nation-state, and that move across borders at will in perpetual search of maximizing profits.

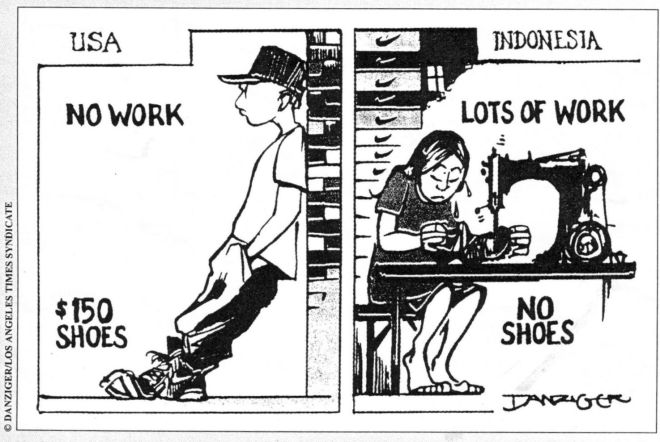

Let me tell you a story about my personal relationship with one of these transnational corporations – Nike. My first pair of serious running shoes were Nikes. Over the years I became so attached to Nikes that I convinced myself that I could not run without wearing them. But once I learned about the conditions under which these shoes are produced, I could not in good conscience buy another pair of their running shoes. It may be true that Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods had multimillion-dollar contracts with Nike, but in Indonesia and Vietnam Nike has been creating working conditions that, in many respects, resemble slavery.

Not long ago there was an investigation of the Nike factory in Ho Chi Minh City, and it was discovered that the young women who work in Nike’s sweatshops there were paid less than the minimum wage in Vietnam, which is only U$2.50 a day… Consider what you pay for Nikes and the vast differential between the price and the workers’ wages. This differential is the basis for Nike’s rising profits. (…) If you read the entire report, you will be outraged to learn of the abominable treatment endured by the young women and girls who produce the shoes and the apparel we wear. The details of the report include the fact that during an 8-hour shift, workers are able to use the toilet just once, and they are prohibited from drinking water more than twice. There is sexual harrasment, inadequate health care, and excessive overtime… Perhaps we need to discuss the possibility of an organized boycott… but given the global reach of corporations like Nike, we need to think about a global boycott.

Corporations move to developing countries because it is extremely profitable to pay workers U$2.50 a day or less in wages. That’s U$2.50 a day, not U$2.50 a hour, which would still be a pittance. (…) The corporations that have migrated to Mexico, Vietnam, and other Third World countries also often end up wreaking havoc on local economies. They create cash economies that displace subsistence economies and produce artificial unemployment. Overall, the effect of capitalist corporations colonizing Third World countries is one of pauperization. These corporations create poverty as surely as they reap rapacious profits.”

(pg. 44-46)

* * * * *

“Free Angela And All Political Prisoners” (2012, download [1.16gb])

[youtube id=http://youtu.be/hdFXaDj0dYk]

* * * * *

“In Wisconsin black people constitute 4 or 5% of the state’s population and about 50% of the imprisoned population. Our criminal justice system sends increasing numbers of people to prison by first robbing them of housing, health care, education, and welfare, and then punishing them when they participate in underground economies. What should we think about a system that will, on the one hand, sacrifice social services, human compassion, housing and decent schools, mental health care and jobs, while on the other hand developing an ever larger and ever more profitable prison system that subjects ever larger numbers of people to daily regimes of coercion and abuse? The violent regimes inside prisons are located on a continuum of repression that includes state-sanctioned killing of civilians.” (The Meaning of Freedom, p. 62)

“It cannot be denied that immigration is on the rise. In many cases, however, people are compelled to leave their home countries because U.S. corporations have economically undermined local economies through ‘free trade’ agreements, structural adjustment, and the influence of such international financial institutions as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Rather than characterize ‘immigration’ as the source of the current crisis, it is more accurate to say that it is the homelessness of global capital that is responsible for so many of the problems people are experiencing throughout the world. Many transnational corporations that used to be required to comply with a modicum of rules and regulations in the nation-states where they are headquartered have found ways to evade prohibitions against cruel, dehumanizing, and exploitative labor practices. They are now free to do virtually anything in the name of maximizing profits. 50% of all of the garments purchased in the U.S. are made abroad by women and girls in Asia and Latin America. Many immigrant women from those regions who come to this country hoping to find work do so because they can no longer make a living in their home countries. Their native economies have been dislocated by global corporations. But what do they find here in the United States? More sweatshops.” (p. 64)

* * * *

“Our impoverished popular imagination is responsible for the lack of or sparsity of conversations on minimizing prisons and emphasizing decarceration as opposed to increased incarceration. Particularly since resources that could fund services designed to help prevent people from engaging in the behavior that leads to prison are being used instead to build and operate prisons. Precisely the resources we need in order to prevent people from going to prison are being devoured by the prison system. This means that the prison reproduces the conditions of its own expansion, creating a syndrome of self-perpetuation.” (p. 67)

“Our impoverished popular imagination is responsible for the lack of or sparsity of conversations on minimizing prisons and emphasizing decarceration as opposed to increased incarceration. Particularly since resources that could fund services designed to help prevent people from engaging in the behavior that leads to prison are being used instead to build and operate prisons. Precisely the resources we need in order to prevent people from going to prison are being devoured by the prison system. This means that the prison reproduces the conditions of its own expansion, creating a syndrome of self-perpetuation.” (p. 67)

“The global war on drugs is responsible for the soaring numbers of people behind bars – and for the fact that throughout the world there is a disproportionate number of people of color and people from the global South in prison. (…) The drug war and the war on terror are linked to the global expansion of the prison. Let us remember that the prison is a historical system of punishment. In other worlds, it has not always been a part of human history; therefore, we should not take this institution for granted, or consider it a permanent and unavoidable fixture of our society. The prison as punishment emerged around the time of industrial capitalism, and it continues to have a particular affinity with capitalism. (…) Globalization has not only created devastating conditions for people in the global South, it has created impoverished and incarcerated communities in the United States and elsewhere in the global North. ” (p. 82)

“Why, in the aftermath of September 11, 2001, have we allowed our government to pursue unilateral policies and practices of global war? (…) Increasingly, freedom and democracy are envisioned by the government as exportable commodities, commodities that can be sold or imposed upon entire populations whose resistances are aggressively suppressed by the military. The so-called global war on terror was devised as a direct response to the September 11 attacks. Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, and George W. Bush swiftly transformed the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon into occasions to misuse and manipulate collective grief, thereby reducing this grief to a national desire for vengeance. (…) It seems to me the most obvious subversion of the healing process occurred when the Bush administration invaded Afghanistan, then Iraq, and now potentially Iran. All in the name of the human beings who died on September 11. Bloodshed and belligerence in the name of freedom and democracy!…

Bush had the opportunity to rehearse this strategy of vengeance and death on a smaller scale before he moved into the White House. As governor of Texas, he not only lauded capital punishment, he presided over more executions – 152 to be precise – than any other governor in the history of the United States of America.

Imperialist war militates against freedom and democracy, yet freedom and democracy are repeatedly invoked by the purveyors of global war. Precisely those forces that presume to make the world safe for freedom and democracy are now spreading war and torture and capitalist exploitation around the globe. The Bush government represents its project as a global offensive against terrorism, but the conduct of this offensive has generated practices of state violence and state terrorism in comparison to which its targets pale…

Estimates range from 500.000 to 700.000 so far – some people say that one million… – people that have been killed during the war in Iraq. Why can’t we even have a national conversation about that?”

“What is most distressing to those of us who believe in a democratic future is the tendency to equate democracy with capitalism. Capitalist democracy should be recognized as the oxymoron that it is. The two orders are fundamentally incompatible, especially considering the contemporary transformations of capitalism under the impact of globalization. But there are those who cannot tell the difference between the two. In no historical era can the freedom of the market serve as an acceptable model of democracy for those who do not possess the means – the capital – to take advantage of the freedom of the market.

The most convincing contemporary evidence against the equation of capitalism and democracy can be discovered in the fact that many institutions with a profoundly democratic impulse have been dismantled under the pressure exerted by international financial agencies, such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. In the global South, structural adjustment has unleashed a juggernaut of privatization of public services that used to be available to masses of people, such as education and health care. These are services that no society should deny its members, services we all should be able to claim by virtue of our humanity. Conservative demands to privatize Social Security in the United States further reveal the reign of profits for the few over the rights of the many.

Another world is possible, and despite the hegemony of forces that promote inequality, hierarchy, possessive individualism, and contempt for humanity, I believe that together we can work to create the conditions for radical social transformation.”

Angela Y. Davis (1944 – )

The Meaning of Freedom

And Other Difficult Dialogues

City Lights Books / Open Media Series

www.citylights.com

San Francisco, California. 2012.

SIGA VIAGEM:

John Lennon e Yoko Ono a ela dedicaram uma canção:

https://youtu.be/Yp9StQhWGdc

https://youtu.be/Yp9StQhWGdc

Publicado em: 20/11/20

De autoria: Eduardo Carli de Moraes